In composing his sonnets, Shakespeare remained wisely circumspect about any specific references to his own life (lots of dangerous stuff goes in the sonnets)–to the point of not even publishing the verses himself. But in Sonnet 111, he gives a hint of a reference to his own life as an actor and why, perhaps he chose that profession:

111

O, for my sake do you with Fortune chide,

The guilty goddess of my harmful deeds,

That did not better for my life provide

Than public means which public manners breeds.

Thence comes it that my name receives a brand,

And almost thence my nature is subdued

To what it works in, like the dyer’s hand:

Pity me then and wish I were renew’d;

Whilst, like a willing patient, I will drink

Potions of eisel ‘gainst my strong infection

No bitterness that I will bitter think,

Nor double penance, to correct correction.

Pity me then, dear friend, and I assure ye

Even that your pity is enough to cure me.

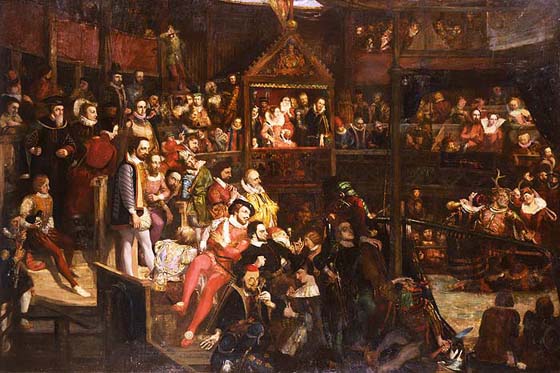

The Young Man apparently blames bad luck–‘Fortune’–for forcing the Poet into such an ignoble profession as ‘public means.’ What does this mean? Some critics and scholars, though not all, believe it’s a reference to Will’s profession as an actor–and that he went into a life of acting to avoid a lot of other awful possibilities for employment in the Elizabethan world. However, though lucrative, acting was not considered a reputable profession in Elizabethan England: women weren’t allowed to act, actors were considered vagrants unless they were licensed under the patronage of a noble (hence Shakespeare’s ‘Lord Chamberlain’s Men’), and the Puritans considered all stagecraft to be the work of the Devil.

Members of the theatre crowd were notorious. ‘Public means’ breeds ‘public manners’, a reference to the ill behavior and bad reputation of theatre rascals, a reputation that’s tainted the Poet: ‘Thence comes it that my name receives a brand.’ If you dig into Shakespeare’s life, you’ll know that after he gained some wealth (by becoming part owner in the actual theatre company he wrote for), he labored mightily to acquire a Coat of Arms for the Shakespeare name, thereby gaining the respect and social station that comes only of being a ‘Gentleman’.

So yes, I know, not everyone agrees that the Sonnets were autobiographical, but there’s some compelling biographical hints in Sonnet 111. Certainly the Young Man would look down on the Poet’s social station as an actor if the Young Man was indeed the 3rd Earl of Southampton, a nobleman. There’s ample circumstantial evidence that the Earl was the Young Man.

The sonnet takes an interesting turn with ‘Potions of eisel ‘gainst my strong infection’ (eisel is vinegar). One of the common dangers of ‘public manners’ was the pox, otherwise known as venereal disease. Venereal disease is revisited in later sonnets with the Dark Lady, and in those there’s little left to the imagination (see numbers 153 & 154). Did Shakespeare at some point in his life contract syphilis? There’s evidence outside of this sonnet that he did, and if that’s the case, then Sonnet 111 teases us with a couple of compelling glimpses into what might’ve been events in the Bard’s life.

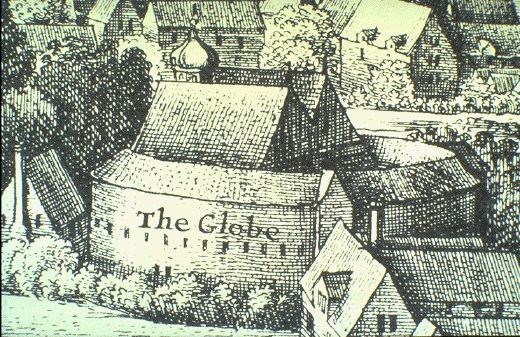

The image comes from a section of Wenceslas Hollar’s 1642 drawing of London, here showing Shakespeare’s rebuilt Globe Theatre.