The pair of novels I’m writing spawned this website: literary fiction mashed up with a bit of science fiction and a bit of mystery: Edgar A. Poe and William Shakespeare. So when a new novel comes along that mashes up genres and starts getting attention, it gets my attention. I just read Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, and if my novels can be only half as good as Ms. Mandel’s, I can die happy.

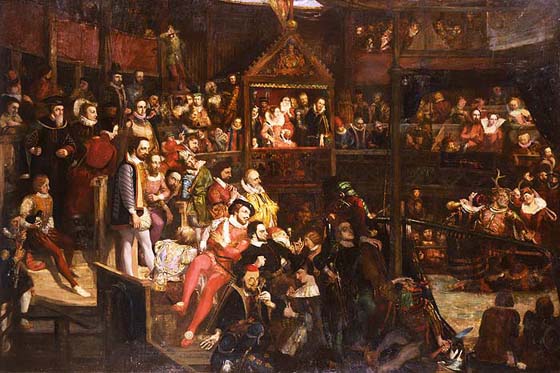

Shakespeare, post-apocalyptic science fiction, a graphic novel, troubled but inspiring female protagonists, religious fanaticism, an intricate web of interconnecting characters, twists of time and even a Star Trek meme, populate this adventure. That makes it seem like a jumble: it’s not. Station Eleven is an elegiac and carefully constructed rumination on the meaning of Art.

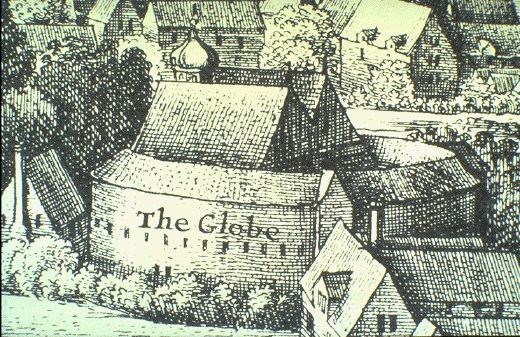

Unlike the too-often utilized post-apocalyptic subgenre, this is book confounds your expectations. It doesn’t hustle along like a Hollywood blockbuster, it takes its time. Page one opens on stage with a production of King Lear. From that point the novel takes you through time and space, before and after a swine-flu mutation obliterates humanity, and all around the globe, into the hearts, hopes and fears of a tableau of characters.

Not to give anything away, but the novel ends where it begins. On the way, if you’re patient with the careful unraveling of events, Mandel rewards you with a series of illuminating connections. Now that I’ve turned the last page, some of these connections seem almost too fantastic to believe: but when you’re in the weave of her fictional dream, these couplings seem amazing, enlightening and uplifting.

Uplifting. A post-apocalyptic novel that’s uplifting! That’s one of the main miracles of this book. And as it’s happening, you completely believe it and buy it.

Take a chance and read this novel. What a wonderful mash up of genres, what a wonderful and poetic journey.