Easter in Shakespeare? It barely exists. Rare are the Shakespearean references to Christianity: yes, members of the clergy are characters, and characters often invoke God, and use events from the Bible as poetic imagery, and as metaphor. Beyond that the Bard largely avoids the issue of Christian Theology.

Was this a reflection of Shakespeare’s own belief? It’d be a mistake to believe that; we really can’t know for certain. But what we do know is that Queen Elizabeth’s flavor of Protestantism was strictly enforced by her government, and it was not a good idea to be Catholic, Jew or Muslim. The other thing we know is that Shakespeare was a savvy businessman and for his own benefit avoided political controversy. Religious theology in Elizabethan England was extremely political.

So if some fool, like Yours Truly, is going to post some Easter blog about the beautiful things Shakespeare wrote about the Easter holiday, he’s going to come up quite short. There’s a one-line reference to the holiday in Romeo and Juliet, and then perhaps some oblique references in other places. That’s about it.

There is, however, one delicious tidbit related to Easter: it’s a reference to the nasty business that went on after the Last Supper and on Good Friday.

In Shakespeare’s history play Richard II, written about 1595, King Richard, near play’s end is facing the end of his Machiavellian reign and dares to compare himself with none other than Jesus Christ:

Yet I well remember

The favours of these men. Were they not mine?

Did they not sometime cry “All hail’ to me?”

So Judas did to Christ. But he in twelve

Found truth in all but one; I in twelve thousand, none.

—Richard II, Act IV

That’s not enough. The disposed Richard takes his bold comparison one step further, from Judas’ betrayal to Pilate’s prosecution:

Though some of you, with Pilate, wash your hands,

Showing an outward pity, yet you Pilates

Have here delivered me to my sour cross,

And water cannot wash away your sin.

—Richard II, Act IV

It was dangerous to put anything religious in print, but in the play Shakespeare could get away with these powerful images invoking Judas, Pilate, Christ and the crucifixion because they were words spoken by a character Shakespeare had managed to make villainous by play’s end. History paints a more ambivalent picture of King Richard II, but for generations, Shakespeare’s play skewed opinion. The powerful evocation of Judas’ betrayal and the Savior’s crucifixion would probably have shocked audiences in the day, all carefully exploited for the purposes of creating exciting drama.

And so while Shakespeare’s works are full of tales and imagery about things destroyed and then coming back to life (i.e., the Easter story), his only direct references to the Passion and Resurrection are the Last Supper betrayal and the Good Friday crucifixion–used to great effect in an impassioned speech by a King who knows he’s doomed.

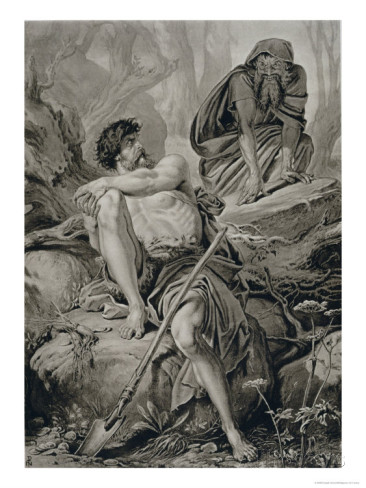

The image is the definitive painting of Richard II, anonymous, now housed in Westminster Abbey.