Today we return to Shakespeare’s early numbered sonnets, almost to the beginning, when the Poet is urging his Young Man to beget a child so that his beauty might be preserved. The poet, in comparing the Young Man to the very ascendancy and brilliance of the Sun itself, could be accused of hyperbole. But when the language is so lovely, perhaps we can forgive the Poet for reaching so high:

7

Lo! in the orient when the gracious light

Lifts up his burning head, each under eye

Doth homage to his new-appearing sight,

Serving with looks his sacred majesty;

And having climbed the steep-up heavenly hill,

Resembling strong youth in his middle age,

Yet mortal looks adore his beauty still,

Attending on his golden pilgrimage:

But when from highmost pitch, with weary car,

Like feeble age, he reeleth from the day,

The eyes, ‘fore duteous, now converted are

From his low tract, and look another way:

So thou, thyself outgoing in thy noon

Unlooked on diest unless thou get a son

If you read through to the end, it’s evident the Sun’s track through the heavens is a metaphor for all people–the passage of human life. And the play on ‘sun’ and ‘son’ is unmistakable.

There’s circumstantial evidence that Shakespeare might’ve been commissioned to write these early sonnets to the young Earl of Southampton, imploring the Young Man to procreate. Who would’ve paid Shakespeare to write these poems for such an unusual reason? It might’ve been none other than Queen Elizabeth’s own chief advisor and Secretary of State, William Cecil, Lord Burghley. Southampton didn’t have a lot of interest in marrying a woman, but it seems he and Shakespeare might’ve had an interest in each other. Later on, the sequence of the Poet’s sonnets to the Young Man move way beyond Burghley’s original (alleged) commission, into the realm of out-and-out romantic love poetry.

All of the prattle about possible historical connections to Sonnet 7 is just one example of Shakespeare’s 154 Sonnets’ historical connections: Beyond the majesty of their poetics and the sheer breadth and depth of being able to compose 154 connected verses, the historical and biographical questions these sonnets raise provide an unending quest for poets, readers, scholars and historians: Why did Shakespeare write 154 of them that when read together weave their own narrative, and why did Shakespeare himself never seek to publicly publish them?

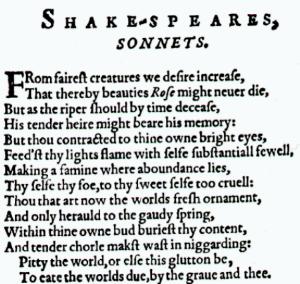

The image is of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, whose connection to Shakespeare we’ll never really know. The painter is anonymous, but the original hangs in Britain’s National Portrait Gallery.