If someone wants (or is forced by a teacher) to study Shakespeare’s challenging Sonnets, perhaps Number 56 is a good place to start. It’s sturdy and straightforward, and talks about something most of us have experienced: a separation from a true love.

56

Sweet love, renew thy force; be it not said

Thy edge should blunter be than appetite,

Which but to-day by feeding is allay’d,

To-morrow sharpen’d in his former might:

So, love, be thou; although to-day thou fill

Thy hungry eyes even till they wink with fullness,

To-morrow see again, and do not kill

The spirit of love with a perpetual dullness.

Let this sad interim like the ocean be

Which parts the shore, where two contracted new

Come daily to the banks, that, when they see

Return of love, more blest may be the view;

Else call it winter, which being full of care

Makes summer’s welcome thrice more wish’d, more rare.

The mention of appetite in the second line is probably talking about lust, and we know lust is like appetite: feed it to satiate it, only to feel it again on the morrow. The love the Poet feels for his Young Man (yes, Number 56 is in the middle of the Young Man sonnets) lingers on through the ‘sad interim’ of their separation, and the big image for this poem is two lovers on two shores with an ocean separating them.

Let this sad interim like the ocean be

Which parts the shore, where two contracted new

Come daily to the banks,

However, if each lover looks hard enough across the ocean, when they do reunite, their coming together will be all the sweeter. Shakespeare then adds another metaphor for the final couplet, comparing the suffering of a long arduous Winter that better prepares us to appreciate Spring. Shakespeare always uses as many metaphors, images and similes as he wants to, whereas we mortals are cautioned to never pile them on. It’s too bad; Elizabethan English was thick with poetic language and Shakespeare was its greatest practitioner.

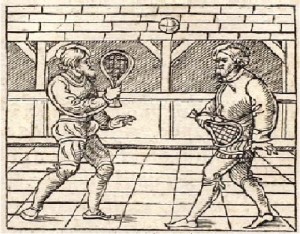

The image (the visual one, not any from the sonnet) comes from an Elizabethan map of the world, circa 1587, by the cartographer Gerard Mercator. His view of the oceans and the globe was not as clear sighted as Shakespeare’s view of love.